Finanzmarkt- und Konzernmacht-Zeitalter der Plutokratie unterstützt von der Mediakratie in den Lobbykraturen der Geld-regiert-Regierungen in Europa, Innsbruck am 02.11.2016

Liebe® Blogleser_in,

Bewusstheit, Liebe und Friede sei mit uns allen und ein gesundes sinnerfülltes Leben wünsch ich ebenfalls.

Aus dieser Quelle zur weiteren Verbreitung entnommen: Aus dieser Quelle zur weiteren Verbreitung entnommen: http://projectcensored.org/1-us-military-forces-deployed-seventy-percent-worlds-nations/

1. US Military Forces Deployed in Seventy Percent of World’s Nations

October 4, 2016

If you throw a dart at a world map and do not hit water, Nick Turse reported for TomDispatch, the odds are that US Special Operations Forces “have been there sometime in 2015.” According to a spokesperson for Special Operations Command (SOCOM), in 2015 Special Operations Forces (SOF) deployed in 147 of the world’s 195 recognized nations, an increase of eighty percent since 2010. “The global growth of SOF missions has been breathtaking,” Turse wrote.

As SOCOM commander General Joseph Votel told the audience of the Aspen Security Forum in July 2015, more SOF troops are deployed to more locations and are conducting more operations than at the height of the Afghan and Iraq wars. In Turse’s words, “Everyday, in around 80 or more countries that Special Operations Command will not name, they undertake missions the command refuses to talk about.”

Calculated in 2014 constant dollars, the SOCOM budget has more than tripled since 2001, when funding totaled three billion dollars. By 2015, SOCOM funding had risen to nearly ten billion dollars. That figure, Turse noted, did not include additional funding from specific military branches, which SOCOM estimated to amount to another eight billion dollars annually, or other undisclosed sums that were not available to the Government Accountability Office.

Every day, Turse wrote, “America’s most elite troops are carrying out missions in 80 to 90 nations.” The majority of these are training missions, “designed to tutor proxies and forge stronger ties with allies.” Training missions focus on everything from basic rifle marksmanship and land navigation to small unit tactics and counterterrorism operations. For example, between 2012–2014, Special Operations Forces carried out 500 Joint Combined Exchange Training (JCET) missions in as many as sixty-seven countries per year. Officially, JCETs are devoted to training US forces, but according to a SOCOM official interviewed by Turse, these missions also “foster key military partnerships with foreign militaries” and “build interoperability between U.S. SOF and partner-nation forces.” JCETs, Turse wrote, “are just a fraction of the story” when it comes to multinational overseas training operations. In 2014, Special Operations Forces organized seventy-five training operations in thirty countries, a figure projected to increase to ninety-eight exercises by the end of 2015, according to the Office of the Under Secretary of Defense.

In addition to training, Special Operations Forces also engage in “direct action.” Counterterrorism missions, including what Turse described as “low-profile drone assassinations and kill/capture raids by muscled-up, high-octane operators,” are the specific domains of Joint Special Operations Command (JSOC) forces, such as the Navy’s SEAL Team 6 and the Army’s Delta Force.

Africa has seen the greatest increase in SOCOM deployments since 2006. In that year, just 1 percent of special operators deployed overseas went to Africa. As of 2014, that figure had risen to 10 percent. In the Intercept, Turse reported on the development by US forces of the Chabelley Airfield in the east African nation of Djibouti. “Unbeknownst to most Americans and without any apparent public announcement,” Turse wrote in October 2015, “the U.S. has recently taken steps to transform this tiny, out-of-the-way outpost into an ‘enduring’ base, a key hub for its secret war, run by the U.S. military’s Joint Special Operations Command (JSOC), in Africa and the Middle East.” Chabelley, he reported, has become “essential” to secret US drone operations over Yemen, southwest Saudi Arabia, Somalia, and parts of Ethiopia and southern Egypt. Aerial images of Chabelley taken between April 2013 and March 2015 testify to the significant expansion of the base and the presence of drones, though officials refused to respond to questions about the number and types of drones based there. As Turse summarized, “The startling transformation of this little-known garrison in this little-known country is in line with U.S. military activity in Africa, where, largely under the radar, the number of missions, special operations deployments, and outposts has grown rapidly and with little outside scrutiny.” (For previous Project Censored coverage of US military operations in Africa, see Brian Martin Murphy, “The ‘New’ American Imperialism in Africa: Secret Sahara Wars and AFRICOM,” in Censored 2014: Fearless Speech in Fateful Times.)

If, as Turse reported, SOCOM has “grown in every conceivable way from funding and personnel to global reach and deployments” since 9/11, has its expansion resulted in significant success? In an October 2015 report for the Nation, Turse reported skepticism from a number of experts in response to this question. According to Sean Naylor, the author of Relentless Strike, a history of Joint Special Operations Command, JSOC operations are “a tool in the policymaker’s toolkit,” not a “substitute for strategy.” JSOC may have had an impact on the history of Iraq—where its forces captured Saddam Hussein, killed Uday and Qusay Hussein, and “eviscerated” Al Qaeda in Iraq—but, as Turse wrote, impacts are not the same as successes. Similarly, Andrew Bacevich, a Vietnam veteran and author of Breach of Trust: How Americans Failed Their Soldiers and Their Country, told Turse, “As far back as Vietnam … the United States military has tended to confuse inputs with outcomes. Effort, as measured by operations conducted, bomb tonnage dropped, or bodies counted, is taken as evidence of progress made. Today, tallying up the number of countries in which Special Operations forces are present repeats this error.”

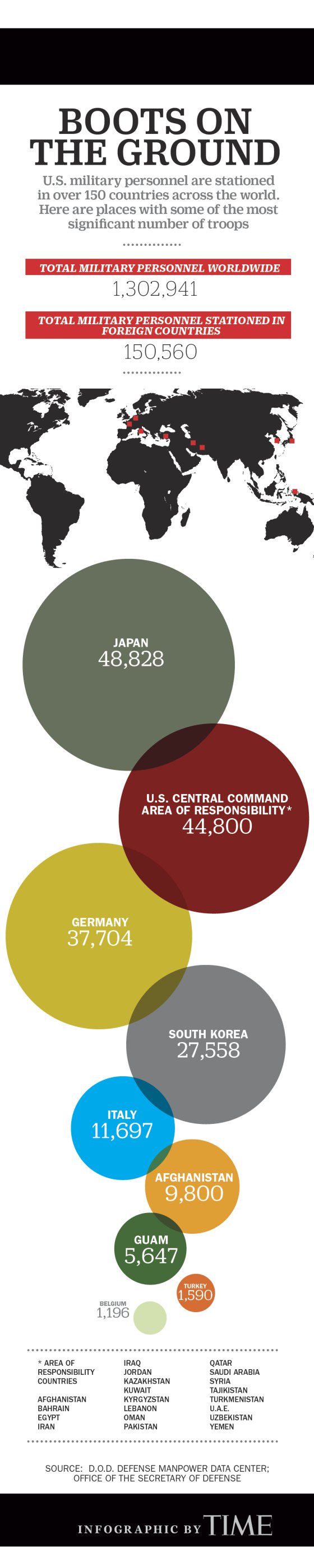

Corporate media have not covered the massive expansion of Special Operations Forces around the globe, much less raised critical questions about whether these missions result in meaningful accomplishments. The increase that has taken place over the past five to ten years is not “breaking” news, and so it has gone all but completely unreported by the corporate press. Instead, the global presence of US military personnel is typically treated as the unspoken background for more dramatic reports of specific military operations or policy decisions. Thus, for example, in October 2015, Time magazine ran a graphic documenting “places with some of the most significant number” of US military personnel stationed “in over 150 countries across the world.” However, the Time map of the world featured just nine points—none of which were located in Africa—and the entire graphic ran as a sidebar to the primary story, about President Obama’s announcement to maintain the current number of troops in Afghanistan through most of 2016, which reversed his earlier plan to withdraw most military personnel by the end of his presidency.

Nick Turse, “A Secret War in 135 Countries,” TomDispatch, September 24, 2015, http://www.tomdispatch.com/blog/176048/.

Nick Turse, “The Stealth Expansion of a Secret US Drone Base in Africa,” Intercept, October 21, 2015, https://theintercept.com/2015/10/21/stealth-expansion-of-secret-us-drone-base-in-africa/.

Nick Turse, “American Special Operations Forces Have a Very Funny Definition of Success,” Nation, October 26, 2015, http://www.thenation.com/article/american-special-operations-forces-have-a-very-funny-definition-of-success/.

Student Researchers: Scott Arrow (Sonoma State University) and Bri Silva (College of Marin)

Faculty Evaluators: Robert McNamara (Sonoma State University) and Susan Rahman (College of Marin)

Aus dieser Quelle zur weiteren Verbreitung entnommen: http://time.com/4075458/afghanistan-drawdown-obama-troops/

————————————————————————————-————

Aus dieser Quelle zur weiteren Verbreitung entnommen: https://theintercept.com/2015/10/21/stealth-expansion-of-secret-us-drone-base-in-africa/

THE STEALTH EXPANSION OF A SECRET U.S. DRONE BASE IN AFRICA

Read the complete Drone Papers.

VIEWED FROM HIGH ABOVE, Chabelley Airfield is little more than a gray smudge in a tan wasteland. Drop lower and its incongruous features start coming into focus. In the sun-bleached badlands of the tiny impoverished nation of Djibouti — where unemployment hovers at a staggering 60 percent and the per capita gross domestic product is about $3,100 — sits a hive of high-priced, high-tech American hardware.

Satellite imagery tells part of the story. A few years ago, this isolated spot resembled little more than an orphaned strip of tarmac sitting in the middle of this desolate desert. Look closely today, however, and you’ll notice what seems to be a collection of tan clamshell hangars, satellite dishes, and distinctive, thin, gunmetal gray forms — robot planes with wide wingspans.

Unbeknownst to most Americans and without any apparent public announcement, the U.S. has recently taken steps to transform this tiny, out-of-the-way outpost into an “enduring” base, a key hub for its secret war, run by the U.S. military’s Joint Special Operations Command (JSOC), in Africa and the Middle East. The military is tight-lipped about Chabelley, failing to mention its existence in its public list of overseas bases and refusing even to acknowledge questions about it — let alone offer answers. Official documents, satellite imagery, and expert opinion indicate, however, that Chabelley is now essential to secret drone operations throughout the region.

Tim Brown, a senior fellow at GlobalSecurity.org and expert on analyzing satellite imagery, notes that Chabelley Airfield allows U.S. drones to cover Yemen, southwest Saudi Arabia, a large swath of Somalia, and parts of Ethiopia and southern Egypt.

“This base is now very important because it’s a major hub for most drone operations in northwest Africa,” he said. “It’s vital. … We can’t afford to lose it.”

The startling transformation of this little-known garrison in this little-known country is in line with U.S. military activity in Africa where, largely under the radar, the number of missions, special operations deployments, and outposts has grown rapidly and with little outside scrutiny.

The expansion of Chabelley and its consequent rise in importance to the U.S. military began in 2013, when the Pentagon moved its fleet of remotely piloted aircraft from its lone acknowledged “major military facility” in Africa — Camp Lemonnier, in Djibouti’s capital, which shares the country’s name — to this lower-profile airstrip about 10 kilometers away.

A hasty perimeter of concertina wire and metal fence posts was constructedaround a bare-bones compound once used by the French Foreign Legion, and the Pentagon asked Congress to fund only “minimal facilities” enabling “temporary operations” there for no more than two years.

But Chabelley would follow a pattern established at Lemonnier. Located on the edge of Djibouti-Ambouli International Airport, Lemonnier also began as an austere location that has, year after year since 9/11, grown in almost every conceivable fashion. The number of personnel stationed there, for example, has jumped from 900 to 5,000 since 2002. More than $600 million has already been allocated or awarded for projects such as aircraft parking aprons, taxiways, and a sizeable special operations compound. It has expanded from 88 acres to nearly 600 acres. Lemonnier is so crucial to U.S. military operations that, in 2014, the Pentagon signed a $70 million per year agreement to secure its lease through 2044.

But as the base grew, the skies over Lemonnier and the adjoining airport became increasingly crowded and dangerous. By 2012, an average of 16 U.S. drones and four fighter jets were taking off or landing there each day, in addition to French and Japanese military aircraft and civilian planes, while local air traffic controllers were committing “errors at astronomical rates,” according to a Washington Post investigation. The Djiboutians were specifically hostile to Americans, ignoring pilots’ communications and forcing U.S. aircraft to circle above the airport until low on fuel — with special ire reserved for drone operations — adding to the havoc in the skies. While the U.S. did not find Djiboutian air traffic controllers responsible, six remotely piloted aircraft based at Lemonnier were destroyed in crashes, including an accident in a residential area of the capital, prompting Djiboutian government officials to voice safety concerns.

As Lemonnier expanded, the Chabelley site underwent its own transformation. Members of the Marines and Army conducted training there during 2008 and, in 2011, troops began work at the base with an eye toward the future. That October, a Marine Air Traffic Control Mobile Team (MMT) undertook efforts to enable a variety of aircraft to use the site. “We provide our commanders the ability to keep the battle line moving forward at a rapid pace,” said Sgt. Christopher Bickel, the assistant team leader of the MMT that worked on the project.

It was in February 2013 that the Pentagon asked Congress to quickly supply funds for “minimal facilities necessary to enable temporary operations” at Chabelley. “The construction is not being carried out at a military installation where the United States is reasonably expected to have a long-term presence,” said official documents obtained by the Washington Post. The next month, before the House Armed Services Committee, then-chief of Africa Command (Africom), Gen. Carter Ham, explained that agreements were being worked out with the Djiboutian government to use the airfield and thanked Congress for helping to hasten things along. “We appreciate the reauthorization of the temporary, limited authority to use operations and maintenance funding for military construction in support of contingency operations in our area of responsibility, which will permit us to complete necessary construction at Chabelley,” he said.

In June 2013, the House Armed Services Committee noted it was “aware that the Government of Djibouti mandated that operations of remotely piloted aircraft (RPA) cease from Camp Lemonnier, while allowing such operations to relocate to Chabelley Airfield, Djibouti.”

But there was another benefit of moving drone operations from the capital to a far less visible locale. In an Air Force engineering publication from the same year, U.S. Air Forces in Europe/Air Forces Africa engineers listed as “significant accomplishments” the development and implementation of plans to shift drones “from Camp Lemonnier to Chabelley Airfield … providing operations anonymity from the International Airport and improving host-nation relations.”

Tim Brown of GlobalSecurity.org notes that Chabelley allows the U.S. to keep its drone missions under much tighter wraps. “They’re able to operate with much less oversight — not completely in secret — but there’s much less chance of ongoing observation of how often drones are leaving and what they’re doing,” he told me recently.

Dan Gettinger, the co-founder and co-director of the Center for the Study of the Drone at Bard College and the author of a guide to identifying drone bases from satellite imagery, agrees. “It seems they started with two CAPs — combat air patrols — about seven aircraft, a mix of Predators and Reapers,” he said. “And since then, we’ve really seen expansion, particularly within the last couple months; a few more hangars and certainly a lot more facilities for personnel at Chabelley.”

By the fall of 2013, the U.S. drone fleet reportedly had been transferred to the more remote airstrip. Africom failed to respond to questions about the number and types of drones based at Chabelley Airfield, but reporting by The Intercept, drawing on formerly secret documents, demonstrates that 10 MQ-1 Predators and four of their larger cousins, MQ-9 Reapers, were based at Lemonnier prior to the move to the more remote site. Neither the Pentagon nor Africom responded to repeated requests by The Intercept for comment on other aspects of drone operations at Chabelley Airfield or the transformation of the outpost into a more permanent facility. The reasons why aren’t hard to fathom.

“These are JSOC and CIA-led missions for the most part,” Gettinger told me recently, conjecturing that the hush-hush operations are likely focused on intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance activities and counterterrorism strikes in Somalia and Yemen, as well as aiding the Saudi-led air campaign in the latter country. Indeed, an Air Force accident report obtained by The Intercept via the Freedom of Information Act details a February 2015 incident in which an MQ-9 “crashed during an intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance mission in the United States Africa Command Area of Responsibility.” The Reaper, assigned to the 33rd Expeditionary Special Operations Squadron operating from Chabelley had flown “about 300 miles away from base” when it began experiencing mechanical problems, according to the pilot. It was eventually ditched in international waters.

Special Operations Command, JSOC’s parent organization, would not comment on Gettinger’s assertions. “We do not have anything for you,” responded spokesperson Ken McGraw.

Despite the supposed temporary nature of the Chabelley site, Africom “directed an expansion of operations” at the airfield and the U.S. inked a “long-term implementing arrangement” with the Djiboutian government to establish Chabelley as a “enduring” base, according to documents provided earlier this year to the House Appropriations Committee by the undersecretary of defense (comptroller). The Air Force also reportedly installed a “tactical automated security system” — a complex suite of integrated sensors, thermal imaging devices, radar, cameras and communications devices — to provide extra layers of protection to the site.

In June, the Pentagon contacted the House Appropriations Committee about reallocating $7.6 million to construct a new 7,720-meter perimeter fence around the burgeoning base, complete with two defensive fighting positions and four pedestrian and five vehicle entry points that also “provides a platform for installing advanced perimeter sensor system equipment.” Last month, defense contractor ECC-MEZZ LLC of Burlingame, California, was awarded a $6.96 million contract for a fence, gates, a perimeter roadway, and a modular guard tower.

Africom remains close-lipped about the expansion and increasing importance of Chabelley. Phone calls and emails seeking comment were ignored. Multiple requests by The Intercept were even “deleted without being read” according to automatic return receipts. After days of also sending requests to Major James Brindle at the Pentagon’s press office, it became apparent that The Intercept isn’t alone in getting the cold shoulder when it comes to America’s preeminent African drone base. A note from Brindle suggested Africom didn’t want to talk to him about Chabelley either. He had apparently passed along my requests only to be similarly ignored. “Still waiting on a reply from Africom. Sorry,” was all he wrote.

—————————————————————————————————–

Aus dieser Quelle zur weiteren Verbreitung entnommen: https://www.thenation.com/article/american-special-operations-forces-have-a-very-funny-definition-of-success/

American Special Operations Forces Have a Very Funny Definition of Success

US Special Operations forces have deployed to 147 countries this year. To what end, exactly?

They’re some of the best soldiers in the world: highly trained, well equipped, and experts in weapons, intelligence gathering, and battlefield medicine. They study foreign cultures and learn local languages. They’re smart, skillful, wear some very iconic headgear, and their 12-member teams are “capable of conducting the full spectrum of special operations, from building indigenous security forces to identifying and targeting threats to U.S. national interests.”

They’re also quite successful. At least they think so.

“In the last decade, Green Berets have deployed into 135 of the 195 recognized countries in the world. Successes in Afghanistan, Iraq, Trans-Sahel Africa, the Philippines, the Andean Ridge, the Caribbean, and Central America have resulted in an increasing demand for [Special Forces] around the globe,” reads a statement on the website of US Army Special Forces Command.

The Army’s Green Berets are among the best known of America’s elite forces, but they’re hardly alone. Navy SEALs, Air Force Air Commandos, Army Rangers, Marine Corps Raiders, as well as civil affairs personnel, logisticians, administrators, analysts, and planners, among others, make up US Special Operations forces (SOF). They are the men and women who carry out America’s most difficult and secret military missions. Since 9/11, US Special Operations Command (SOCOM) has grown in every conceivable way from funding and personnel to global reach and deployments. In 2015, according to Special Operations Command spokesman Ken McGraw, US Special Operations forces deployed to a record-shattering 147 countries—75 percent of the nations on the planet, which represents a jump of 145 percent since the waning days of the Bush administration. On any day of the year, in fact, America’s most elite troops can be found in 70 to 90 nations.

There is, of course, a certain logic to imagining that the increasing global sweep of these deployments is a sign of success. After all, why would you expand your operations into ever-more nations if they weren’t successful? So I decided to pursue that record of “success” with a few experts on the subject.

I started by asking Sean Naylor, a man who knows America’s most elite troops as few do and the author of Relentless Strike: The Secret History of Joint Special Operations Command, about the claims made by Army Special Forces Command. He responded with a hearty laugh. “I’m going to give whoever wrote that the benefit of the doubt that they were referring to successes that Army Special Forces were at least perceived to have achieved in those countries rather than the overall US military effort,” he says. As he points out, the first post-9/11 months may represent the zenith of success for those troops. The initial operations in the invasion of Afghanistan in 2001–carried out largely by US Special Forces, the CIA, and the Afghan Northern Alliance, backed by US airpower—were “probably the high point” in the history of unconventional warfare by Green Berets, according to Naylor. As for the years that followed? “There were all sorts of mistakes, one could argue, that were made after that.” He is, however, quick to point out that “the vast majority of the decisions [about operations and the war, in general] were not being made by Army Special Forces soldiers.”

For Linda Robinson, author of One Hundred Victories: Special Ops and the Future of American Warfare, the high number of deployments is likely a mistake in itself. “Being in 70 countries…may not be the best use of SOF,” she told me. Robinson, a senior international policy analyst at the Rand Corporation, advocates for a “more thoughtful and focused approach to the employment of SOF,” citing enduring missions in Colombia and the Philippines as the most successful special ops training efforts in recent years. “It might be better to say ‘Let’s not sprinkle around the SOF guys like fairy dust.’ Let’s instead focus on where we think we can have a success.… If you want more successes, maybe you need to start reining in how many places you’re trying to cover.”

Most of the special ops deployments in those 147 countries are the type Robinson expresses skepticism about—short-term training missions by “white” operators like Green Berets (as opposed to the “black ops” man-hunting missions by the elite of the elite that captivate Hollywood and video gamers). Between 2012 and 2014, for example, Special Operations forces carried out 500 Joint Combined Exchange Training (JCET) missions in as many as 67 countries, practicing everything from combat casualty care and marksmanship to small unit tactics and desert warfare alongside local forces. And JCETs only scratch the surface when it comes to special ops missions to train proxies and allies. Special Operations forces, in fact, conduct a variety of training efforts globally.

A recent $500 million program, run by Green Berets, to train a Syrian force of more than 15,000 over several years, for instance, crashed and burned in a very public way, yielding just four or five fighters in the field before being abandoned. This particular failure followed much larger, far more expensive attempts to train the Afghan and Iraqi security forces in which Special Operations troops played a smaller yet still critical role. The results of these efforts recently prompted TomDispatch regular and retired Army colonel Andrew Bacevich to write that Washington should now assume “when it comes to organizing, training, equipping, and motivating foreign armies, that the United States is essentially clueless.”

THE ELITE WARRIORS OF THE WARRIOR ELITE

In addition to training, another core role of Special Operations forces is direct action–counterterror missions like low-profile drone assassinationsand kill/capture raids by muscled-up, high-octane operators. The exploits of the men–and they are mostly men (and mostly Caucasian ones at that)–behind these operations are chronicled in Naylor’s epic history of Joint Special Operations Command (JSOC), the secret counterterrorism organization that includes the military’s most elite and shadowy units like the Navy’s SEAL Team 6 and the Army’s Delta Force. A compendium of more than a decade of derring-do from Afghanistan to Iraq, Somalia to Syria, Relentless Strike paints a portrait of a highly-trained, well-funded, hard-charging counterterror force with global reach. Naylor calls it the “perfect hammer,” but notes the obvious risk that “successive administrations would continue to view too many national security problems as nails.”

When I ask Naylor about what JSOC has ultimately achieved for the country in the Obama years, I get the impression that he doesn’t find my question particularly easy to answer. He points to hostage rescues, like the high profile effort to save “Captain Phillips” of the Maersk Alabama after the cargo ship was hijacked by Somali pirates, and asserts that such missions might “inhibit others from seizing Americans.” One wonders, of course, if similar high-profile failed missions since then, including the SEAL raid that ended in the deaths of hostages Luke Somers, an American photojournalist, and Pierre Korkie, a South African teacher, as well as the unsuccessful attempt to rescue the late aid worker Kayla Mueller, might then have just the opposite effect.

“Afghanistan, you’ve got another fairly devilish strategic problem there,” Naylor says, and offers up a question of his own: “You have to ask what would have happened if Al Qaeda in Iraq had not been knocked back on its heels by Joint Special Operations Command between 2005 and 2010?” Naylor calls attention to JSOC’s special abilities to menace terror groups, keeping them unsteady through relentless intelligence gathering, raiding, and man-hunting. “It leaves them less time to take the offensive, to plan missions, and to plot operations against the United States and its allies,” he explains. “Now that doesn’t mean that the use of JSOC is a substitute for a strategy… It’s a tool in a policymaker’s toolkit.”

Indeed. If what JSOC can do is bump off and capture individuals and pressure such groups but not decisively roll up militant networks, despite years of anti-terror whack-a-mole efforts, it sounds like a recipe for spending endless lives and endless funds on endless war. “It’s not my place as a reporter to opine as to whether the present situations in Afghanistan, Iraq, and Yemen were ‘worth’ the cost in blood and treasure borne by U.S. Special Operations forces,” Naylor tells me in a follow-up email. “Given the effects that JSOC achieved in Iraq (Uday and Qusay Hussein killed, Saddam Hussein captured, [Al Qaeda in Iraq leader Abu Musab] Zarqawi killed, Al Qaeda in Iraq eviscerated), it’s hard to say that JSOC did not have an impact on that nation’s recent history.”

Impacts, of course, are one thing, successes another. Special Operations Command, in fact, hedges its bets by claiming that it can only be as successful as the global commands under which its troops operate in each area of the world, including European Command, Pacific Command, Africa Command, Southern Command, Northern Command, and Central Command or CENTCOM, the geographic combatant command that oversees operations in the Greater Middle East. “We support the Geographic Combatant Commanders (GCCs)–if they are successful, we are successful; if they fail, we fail,” says SOCOM’s website.

With this in mind, it’s helpful to return to Naylor’s question: What if Al Qaeda in Iraq, which flowered in the years after the US invasion, had never been targeted by JSOC as part of a man-hunting operation going after its foreign fighters, financiers, and military leaders? Given that the even more brutal Islamic State (IS) grew out of that targeted terror group, that IS was fueled in many ways, say experts, both by US actions and inaction, that its leader’s rise was bolstered by US operations, that “U.S. training helped mold” another of its chiefs, and that a US prison served as its “boot camp,” and given that the Islamic State now holds a significant swath of Iraq, was JSOC’s campaign against its predecessor a net positive or a negative? Were special ops efforts in Iraq (and therefore in CENTCOM’s area of operations)–JSOC’s post-9/11 showcase counterterror campaign–a success or a failure?

Naylor notes that JSOC’s failure to completely destroy Al Qaeda in Iraq allowed IS to grow and eventually sweep “across northern Iraq in 2014, seizing town after town from which JSOC and other U.S. forces had evicted al-Qaeda in Iraq at great cost several years earlier.” This, in turn, led to the rushing of special ops advisers back into the country to aid the fight against the Islamic State, as well as to that program to train anti-Islamic State Syrian fighters that foundered and then imploded. By this spring, JSOC operators were not only back in Iraq and also on the ground in Syria, but they were soon conducting drone campaigns in both of those tottering nations.

This special ops merry-go-round in Iraq is just the latest in a long series of fiascos, large and small, to bedevil America’s elite troops. Over the years, inthat country, in Afghanistan, and elsewhere, special operators haveregularly been involved in all manner of mishaps, embroiled in variousscandals, and implicated in numerous atrocities. Recently, for instance, members of the Special Operations forces have come under scrutiny for an air strike on a Médecins Sans Frontières hospital in Afghanistan that killedat least 22 patients and staff, for an alliance with “unsavory partners” in the Central African Republic, for the ineffective and abusive Afghan police they trained and supervised, and for a shady deal to provide SEALs with untraceable silencers that turned out to be junk, according to prosecutors.

WINNERS AND LOSERS

JSOC was born of failure, a phoenix rising from the ashes of Operation Eagle Claw, the humiliating attempt to rescue 53 American hostages from the US Embassy in Iran in 1980 that ended, instead, in the deaths of eight US personnel. Today, the elite force trades on an aura of success in the shadows. Its missions are the stuff of modern myths.

In his advance praise for Naylor’s book, one cable news analyst called JSOC’s operators “the finest warriors who ever went into combat.” Even accepting this–with apologies to the Mongols, the Varangian Guard, Persia’s Immortals, and the Ten Thousand of Xenophon’s Anabasis–questions remain: Have these “warriors” actually been successful beyond budget battles and the box office? Is exceptional tactical prowess enough? Are battlefield triumphs and the ability to batter terror networks through relentless raiding the same as victory? Such questions bring to mind an exchange that Army colonel Harry Summers, who served in Vietnam, had with a North Vietnamese counterpart in 1975. “You know, you never defeated us on the battlefield,” Summers told him. After pausing to ponder the comment, Colonel Tu replied, “That may be so. But it is also irrelevant.”

So what of those Green Berets who deployed to 135 countries in the last decade? And what of the Special Operations forces sent to 147 countries in 2015? And what about those Geographic Combatant Commanders across the globe who have hosted all those special operators?

I put it to Vietnam veteran Andrew Bacevich, author of Breach of Trust: How Americans Failed Their Soldiers and Their Country. “As far back as Vietnam,” he tells me, “the United States military has tended to confuse inputs with outcomes. Effort, as measured by operations conducted, bomb tonnage dropped, or bodies counted, is taken as evidence of progress made. Today, tallying up the number of countries in which Special Operations forces are present repeats this error. There is no doubt that US Special Operations forces are hard at it in lots of different places. It does not follow that they are thereby actually accomplishing anything meaningful.”

————————————————————————————————————————————-

Aus dem per ÖVP-Amtsmissbräuche offenkundig verfassungswidrig agrar-ausgeraubten Tirol, vom friedlichen Widerstand, Klaus Schreiner

Don´t be part of the problem! Be part of the solution. Sei dabei! Gemeinsam sind wir stark und verändern unsere Welt! Wir sind die 99 %!

“Wer behauptet, man braucht keine Privatsphäre, weil man nichts zu verbergen hat, kann gleich sagen man braucht keine Redefreiheit weil man nichts zu sagen hat.“ Edward Snowden

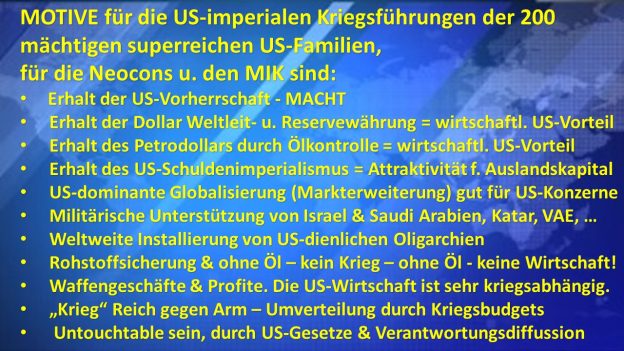

PDF-Downloadmöglichkeit eines wichtigen sehr informativen Artikels über den amerikanischen Militärisch-industriellen-parlamentarischen-Medien Komplex – ein Handout für Interessierte Menschen, die um die wirtschaftlichen, militärischen, geopolitischen, geheimdienstlichen, politischen Zusammenhänge der US-Kriegsführungen samt US-Kriegspropaganda mehr Bescheid wissen wollen :

————————————————————————————-————

Hier noch eine kurzes Video zur Erklärung der Grafik Gewaltspirale der US-Kriege

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1PnxD9Z7DBs

Ein wirklich sehr empfehlenswertes aufklärendes Buch:

Aktivist4you empfiehlt wärmsten das unabhängige Magazin www.free21.org zu unterstützen bzw. zu abonnieren.

Bitte teile diesen Beitrag: